Croatian Easter traditions thrive in Peru

Peruvians of Croatian descent met in Lima for Easter to observe this religious holiday in accordance with traditional Croatian customs.

The celebration was organised at the Croatian Association Dubrovnik, founded in 1906, and the Croatian Cultural Club "Jadran" (Adriatic), established in 1951, bringing together around 200 Croats and their descendants, CE Report quotes HINA.

Father Drago Balvanović led the blessing of the food and the decorated Easter eggs, lovingly prepared by members of the community in the days leading up to the event.

At the Dubrovnik Association, named after the city from which the first Croats likely arrived, possibly in search of gold in the 16th century among the Spaniards, guests sat grouped in tables of ten, enjoying the warmth of community and tradition. One of the most beloved customs quickly brought laughter to the room: egg tapping, or "tucanje pisanicama" in Croatian.

Among those taking part was 18-year-old Alejandra Giraldo, born in Lima, who hesitated for a moment, unsure of how to properly strike her egg against her opponent’s. With a smile and some guidance from the older members, she soon got the hang of it.

"I didn’t know which side of the egg to use!" she laughed, holding up her now-cracked pisanica. "But it’s fun—like a game and a story at the same time."

Giraldo is a sixth-generation descendant of Croatian emigrants, raised among Peruvians, but thanks to gatherings at the association, she is gradually embracing Croatian customs and traditions.

"Here I learn things I wouldn’t hear anywhere else," she said. "It helps me feel connected to a part of my identity that I’m still discovering."

A group of children under the age of ten spent Sunday eagerly hunting for hidden plastic eggs in the garden of the Croatian association. Among them was Fabrizio Valencia, proudly dressed in a Croatian national football team jersey bearing the name (Marko) Livaja.

“He really loves football and watches the Croatian national team on TV,” said his mother, 48-year-old Marisol Esparza, with a smile.

“His grandmother brought him (footballer Marko) Livaja’s jersey from Croatia, even though he really wanted (Luka) Modrić’s,” she added, laughing.

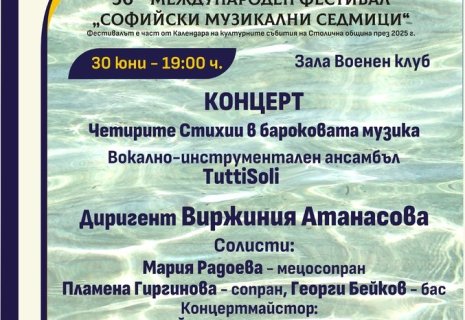

Easter celebrated by Croatian Cultural Club Jadran

Members of the Croatian Cultural Club Jadran, whose ancestors arrived in Peru after the Second World War, celebrated Easter at the Parish of Saint Leopold.

In this Croatian church, adorned with the Croatian flag and portraits of Blessed Alojzije Stepinac and Saint Blaise, they took time to reflect on the difficult journey their grandparents endured upon arriving on the shores of Peru.

Far from their homeland, they proudly displayed small Croatian flags and came together in prayer, united by faith and heritage.

A key challenge for Croatian associations today is how to engage younger generations and strengthen their connection with Croatia.

For Diana Manrique Kukurelo, a 26-year-old diplomat at Peru’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, that connection became tangible when she visited Croatia for the first time in 2023 and discovered that she had living relatives there.

"I’m happy to have uncovered that part of my past on the other side of the world," she said. "I’m Peruvian, but equally proud of my Croatian heritage."

Her story reflects the quiet but profound journey of rediscovery many descendants of Croatian emigrants are making, bridging continents, cultures, and generations through identity, memory, and the enduring spirit of community.

An estimated 6,000 Croats and their descendants live in Peru

In Peru, a country of 34.8 million people, around 6,000 Croats and their descendants live, according to the Central State Office for Croats Abroad. However, research by honorary Croatian consul Ana María Kuljevan suggests that the actual number is significantly higher.

Peru was the first South American country to which Croats arrived, back in the 16th century. In 1573, Dubrovnik nobleman Basilije Basiljević, like thousands of other Europeans, set off to try his luck in South America.

Larger numbers of Croats began arriving in Peru in the second half of the 19th and early 20th centuries. These were mostly people from Dubrovnik, with some coming from other parts of Dalmatia and the coastal region.

In the late 19th century, the export of natural guano fertiliser was booming, and some Croatian emigrants tried their luck in that industry. With the end of colonial rule and the establishment of the Republic of Peru, the country began developing its mining sector, which encouraged Croats to head into the Andes and engage in the extraction of copper, gold, and silver.

By the late 19th century, Croats, mainly from the Dubrovnik region, had become a prominent foreign community in Cerro de Pasco, a city in central Peru, located at the top of the Andean Mountains.

A smaller number of Croats arrived after the First World War. Then, in 1948, following the Second World War, a group of around 1,000 Croatian political emigrants from across Croatia settled in Peru.